How genetics impact your education?

Prof. King Chow, Division of Life Science, tells you why genes do not completely dictate how well you fare in school.

By Prof. King Chow, Division of Life Science, HKUST

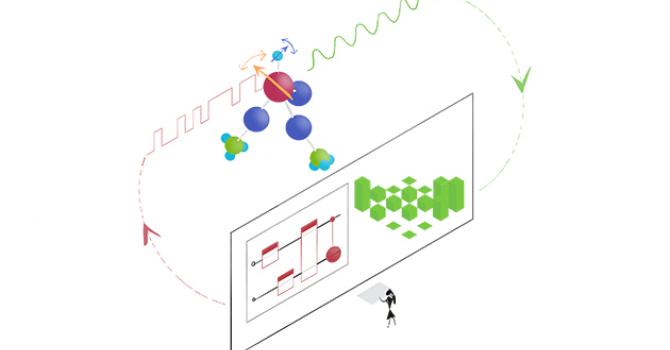

Previously, my colleague Dr. Melody Leung explored the issue of gene editing babies, which may have prompted some parents to ask one question – Can we make children fonder of school with genetic engineering? An international research team published in the scientific journal Nature Genetics last August a genome-wide association study conducted on 1.1 million individuals from 15 countries. They found that more than 1,200 genetic variants are associated with educational attainment.

Judging from the variants on their own merits, the results of this study demonstrate that education attainment is only partly heritable – if a parent has certain genetic variants, his or her child is more likely to stay in school longer. However, most variants in behavior cannot be explained based on genetics alone. In other words, there may be a certain correlation between a particular genetic variant and a person’s behavior (be attentive, more willing to work in groups, for example), but this relationship is by no means causal.

Actually, as pointed out in the study, when scientists included the effects of all of the variants across the genome to develop a new polygenic score, the score was only predictive of 11 to 13 percent of variation in years of completed schooling, making the score's predictive power for educational attainment no better than that of demographic factors, like financial status of the family, school environment or supportive parents, etc.

To that end, the debate of nature versus nurture provides us with a better understanding of why we do what we do. Genes-wise, having certain genetic variants would be advantageous, and the more so the more advantages they will add. But it is not about solving a problem faster or slower – the question is whether the individual has the ability to solve the problem at all. Born into a certain environment is less restrictive than born with a gene – and indeed, the former can be altered more easily with proper social policies implemented by the government or parental care. For example, one’s decision to pursue a degree of medicine or not has much to do with the resources he or she has and the influence by their parents and peers, and not so much with whether he has the gene to excel in the profession.

At the end, the study provides an excellent example of how we cannot predict educational outcome from genes. The best way to achieve good performance in schools lies not only on our genes but more in the hands of policymakers: how do we create an environment where youngsters with different capabilities can be supported to excel in what they do best, rather than solely measuring their achievement by standardized test scores? Can we cherish variety, even when the dominant culture in Hong Kong may prefer otherwise? These will be questions for us all.